In an age torn apart by the culture wars between science and religion, Catholic theologian John Haught has a better way. Here, EnlightenNext offers a glimpse inside the prodigious mind and heart of a man who has looked into the future and seen a new face of God.

“Turn right in five hundred yards.” The words rang out in my car, like the booming, disembodied voice of some divine authority, this one filled with infallible knowledge of all possible future roads that I might ever travel. For a moment I felt like Moses, except that in this case the burning bush was simply my new navigation system, sounding out voice commands, directing my every move through the heavy July traffic on Long Island. I was headed to Sag Harbor, a beautiful old fishing village turned artist colony on the eastern edge of Long Island, to meet with John Haught, a Catholic theologian from Georgetown University. Haught was temporarily staying in a Catholic retreat center on the coast, leading a weeklong course on “The New Cosmic Story.”

Last spring, I had contacted Haught requesting an interview on the subject of his latest book, God and the New Atheism: A Critical Response to Dawkins, Harris, and Hitchens. He agreed, and soon I rang him up and asked my first question. Fifteen minutes later, I stopped him mid-sentence. Now generally, a fifteen-minute answer from an interviewee is not a particularly good sign and precedes a desperate attempt to get the interview back on track. But Haught was different. His words were clear and precise; his command of the subject, profound; and his train of thinking, sensible and deeply rational. And this wasn’t just in regard to atheism, faith, and unbelief. His rich and multilayered responses hinted at a much deeper and broader theological agenda—to define and articulate a new vision for the religious impulse in the twenty-first century. I had come across Haught’s work before, looked through his books Deeper Than Darwin and God After Darwin, heard fellow editors refer to his work in positive terms, even watched brief videos of him on science-and-spirit websites. But this was the first time I had actually spoken to the man himself. By the time the interview was finished an hour later, I had come to a resolution—I needed to find out more about what made this unusual theologian tick and why his thoughts about God were so compelling.

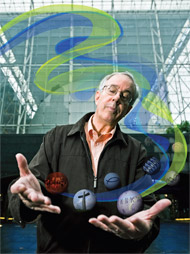

On the surface, Haught might appear quite conventional, even traditional—a simple bespectacled academic with a strong interest in the relationship between science and spirit. But appearances can be deceiving. The more I learned, the more I began to understand that Haught’s mainstream credentials were in fact concealing a much more interesting subtext—a more subversive subplot, if you will. Indeed, those of us who have come of age in a Western spiritual climate largely influenced by the influx of Eastern enlightenment traditions sometimes have a harder time recognizing spiritual and religious innovation when it comes clothed in the conventions of our own culture’s faiths. Haught is certainly a Christian, and he easily speaks the language of faith, God, and belief. But he is also emerging as a significant player in a larger spiritual project, one that transcends and includes any specific tradition. We live in a time when teachers, thinkers, and philosophers are attempting to articulate, understand, and ultimately define a truly post-traditional spiritual worldview that could survive and thrive in a scientific age. In the pages of this magazine, we have called the early fruits of that project “evolutionary spirituality.” Haught calls his offering to that emerging tradition “evolutionary theology.” By whatever name, these new approaches are shaking the pillars of tradition and recontextualizing the way we understand both science and religion.

Seven hundred fifty years ago, Thomas Aquinas penned his masterpiece Summa Theologica, combining the philosophy of Aristotle, Augustine, and many of the best Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and even pagan ideas of the time into a grand reinvention of Christian thought. Today we are tasked with a similar need to reinvent our own traditions for a world vastly changed. How was Haught’s evolutionary theology, I wondered, helping to serve that project? Curious to meet the voice on the other end of the phone, I headed east toward Long Island, that summer mecca of sun and sand, searching for answers with only my trusty navigator to guide my way.

“Destination ahead,” the navigator’s voice sounded off as I slowly made my way up the driveway of a beautiful oceanside property that looked as if it had truly been blessed by some divine touch. Haught had invited me to the retreat center for the day, both to watch him teach and in the hope that a relaxed schedule would allow ample time for interview and dialogue. I found him in the main dining room, one man amid a large roomful of nuns—or so I was told. There was not a habit among them, or any obvious signs of their faith. But over the course of the afternoon, I came to understand that these were likely some of the most progressive sisters in the Church—smart, sophisticated, many a professor among them, and all interested in hearing how our changing understanding of the cosmos was reinventing the religion they had dedicated their lives to.

Haught introduced himself and shook my hand—a tall, somewhat gangly man who seemed to combine a professorial seriousness with a grandfatherly sweetness. I liked him immediately, and he ushered me over to a table, where we fell deep into conversation.

“We have plenty of time to talk,” he began. “The next session doesn’t start until mid-afternoon.” Chuckling softly, he added, “That’s a sure sign it’s a Catholic retreat and not a Protestant one. Protestants have that work ethic—they start early and end late. Catholics, well … it’s different.”